This year is coming to its end, my December posting is precisely the 25th day before Christmas.

While I hope and pray that my friends and family will experience peace and love during this Christmas of 2023, we all know that this is not the total story of the first Christmas.

Mary and Joseph, whose story we celebrate, were homeless as Mary went into labour. A stable provided shelter for a while but beyond that they became refugees escaping to Egypt; a refugee family with a new-born baby. Their child was specifically targeted to be slain.

I’m a fan of Joseph of course: irritated that he is often pictured with a lily in his hand; proud of the depth of his reflection, his courage in a politically fraught near-impossible situation. Tough love in action.

The scripture records that the child grew ‘in age, grace and wisdom’. The parents faced challenge after challenge. Reading forward it seems to me that the parents grew ‘in age grace and wisdom’ too. The challenges they faced must have stretched them to the limit.

Our media this year is awash with stories of families in the same circumstance, facing death and danger, guarding their children with all the love they can muster.

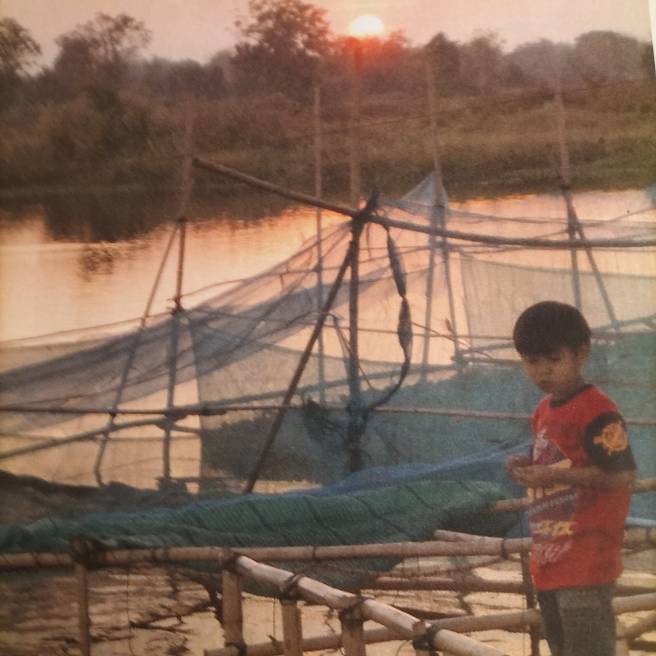

Years ago, in Cambodia, I watched at close range families making gut-wrenching decisions: weighing the choices; discerning the consequences; life or death. As danger escalated, they were stretched to do more than they ever could have imagined.

These stories live on in my memory.

It is the dry season, in Battambang, the time for tanks and armoured vehicles to roll easily into attack. The Khmer Rouge forms a tight ring around Battambang town; already they have shelled the main bridge across our river. A friend, Nee, the father of a young family, brings his two little children to ‘the field of kick the ball’ while their mother and grandmother are busy at home with the new baby. We sit together, there on a patch of grass striped with rays of sunshine and shade, while Nee laughs with his daughter and son as if he has no care in the world. They join the laughter as they take turns to come up close behind their father’s back. He lifts them one by one in the air, they somersault shrieking with delight before he guides them down and around until they stand on their feet facing him. Nee knows that back at the house a pushcart is packed and ready, as heavy as he can push. He expects that in the next few days they will be on the road again; right now, the little ones deserve this joy. Tomorrow or the next day Nee will be responsible for the lives of the baby, the two children, his wife and his mother-in-law on the open road in a war zone. Something great in human nature brings compassion to the fore. I call it love.

In Wat Kundung, my village, the houses are tight packed like a hand full of toy houses dropped from a child’s box of wooden toys. If I sit at the top of the ladder to my one roomed house on stilts, my doorway is about five meters away from the doorway of a house facing mine.

I love early morning, the dawn time. I light my candle while it is still dark, then one by one candles light in other doorways. A thread of light links my life with the life of others.

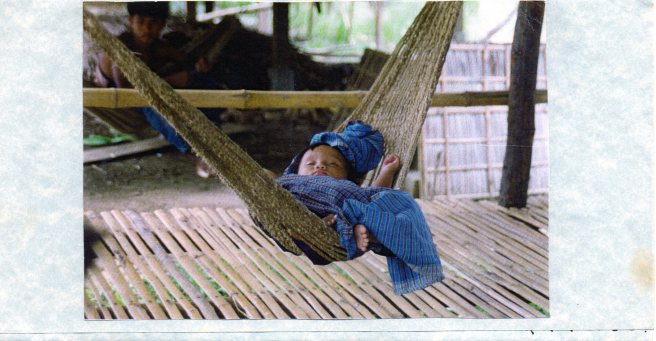

My neighbour, Talika, is a young woman who has lost one leg to a landmine, while she valiantly manages alone with a baby. Her doorway faces mine. She sings a lullaby to the baby in the night, I can hear every word of it. In the morning as she lights her candle, sings again. With the baby in her arms she edges herself down the ladder of her house on stilts, sitting on each step and levering herself to the next. Balancing on one leg and a crutch, she stands by the water pot, and wrapped in a sarong pours water over her head, smoothing the soap suds down to the wooden platform where she stands. Then she holds her baby aloft, bathes him with the soap suds and the water from the pot. Coolness after a hot night! Their laughter fills our space. I call it love; she calls it compassion.

I watch it again and again. Inbuilt resilience, fierce safeguarding. More obvious in the darkest times. One of my favorite poets, Judith Wright, would have something to say about this.

I have known a wine

a drunkenness that can’t be spoken or sung

without betraying it.

For past Yours or Mine even past Ours,

it has nothing at all to say;

it slants a sudden laser through common day

… Maybe there was once a word for it.

Call it grace.

I