Let me write you a story that I should have written long ago.

It starts early in 1975. The city of Phnom Penh in Cambodia is seriously overcrowded with families from the countryside fleeing from war, seeking safety wherever they can find it. The Khmer Rouge rebel army is pushing towards the capital and controls most of the countryside. The government troops are fast running out of ammunition. The USA has withdrawn its support.

French missionaries, guided by their Embassy, are among the few who expect that when the capital falls there will be a time of terror. Cambodian-born priests urge the French missionaries to leave immediately. These Cambodians will stay. None of them survive the terror to come. I have heard that they numbered thirty-two but cannot check this. They knew their danger; they had a way to escape. They chose to stay.

The Catholic population, though small in number, had erected churches throughout the country; in Phnom Penh there was a gothic Cathedral that could seat 10,000 people. During Khmer Rouge times no stone was left upon a stone, not in the capital, not in the regions.

The Cambodian people suffered a reign of terror until 1979. Two in seven Cambodians would die. All would be traumatised.

In 1991 I was sent into Battambang. There were few foreigners working there. The Cambodians I worked among arranged for me to come to the Sunday Mass.

Let me take you there. It is a typical house-on-stilts near the rice fields. There is one main room upstairs and a shady space beneath the house used as the cooking place. The expanse of cleared earth surrounding the house is swept each morning to ensure that no small biting creatures came close to the threshold. Near the ladder that gives access to the upstairs room there is a water-pot with a plastic bowl floating there, ready to serve as a dipper-shower-bathroom for the family.

A great number of women, men and children are sitting on the ground in the clearing, Khmer style. I am invited up the ladder. Here people, mainly women, are sitting on the timber floor. It seems to me that every smidgen of space is taken, but they move closer together to make space for one more. The crowd swells below. The loudspeaker is tested. Everyone can hear; everyone can see.

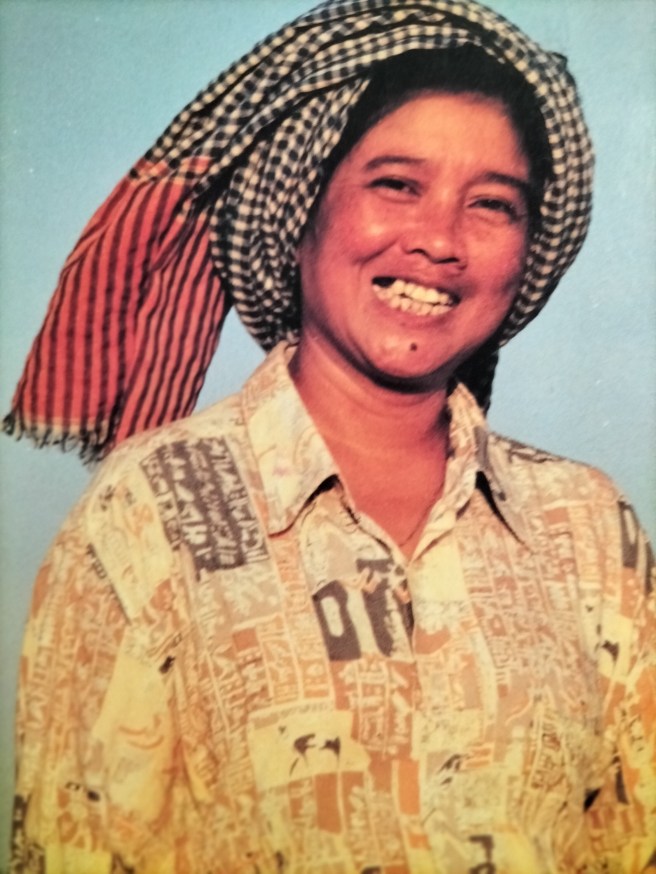

We sing the hymns in Khmer. We listen to the readings in Khmer, exactly the Sunday readings for the day. A woman gives the sermon. Another woman leads the praying; she knows the needs of this community and the needs of the country. I watch the crowd below as they listen, and they sing. They have suffered in ways I now know well. They are still not far from the frontline of the Khmer Rouge fighters; we often hear the distant boom of shelling. Their famous Battambang cathedral is gone, but they continue. They are the Church.

In the weeks and months that follow I watch these women. They baptise, they preside over weddings, they preside over funerals. What needs to be done in the Catholic Church is led by women. I learn later that this is not the first time that the Catholic Cambodians have taken the lead as they see fit in times of crisis.

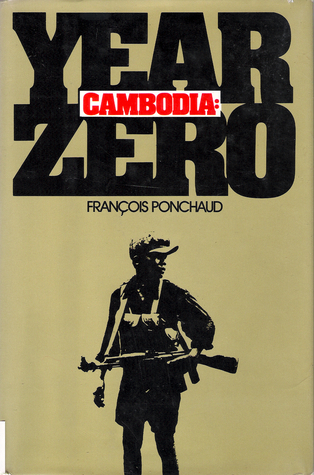

I knew of Francois Ponchaud, a French priest, who was in Phnom Penh and was held in detention when the country fell into the hands of the Khmer Rouge. He spoke fluent Khmer and at 36 years old was a keen observer of the systemic abuse carried out by the Khmer Rouge as the whole population was forced out onto the roads. He had spent three years national service in Algeria as a paratrooper during the Algerian War and returned to his studies in 1961, becoming a Jesuit. He spoke for justice; perhaps that was why he was detained before leaving.

After Francois and the last few foreigners left Cambodia, contact with the outside world was cut off. The Khmer Rouge abolished private ownership, currency, schools, markets and Buddhist monasteries. They emptied towns. They named the new start Year Zero.

When he returned to France, Francois Ponchaud published a three-page article on what he had seen and heard during the brutal evacuation of Phnom Penh. This was not widely read or believed. Knowing that the world needed to hear what he had witnessed he wrote a book: Cambodia Year Zero. Published in 1977 it was acclaimed as essential reading for those seeking to understand what was happening in Cambodia. Very gradually the world became aware of the regime of the Khmer Rouge. Many more books followed; Francois Ponchaud is respected for his balanced accounting of this history. In 2013 he was called back to Cambodia to give evidence at the United Nations War Crimes Tribunal. After being questioned day after day Francois Ponchaud gave his opinion that the ones on trial should have been Kissinger and Nixon.

Francois wrote a book exploring four centuries of the history of the Catholic Church in Cambodia; the title is ‘The Cathedral of the Ricefields’. Those Catholic women of the Battambang showed me their own cathedral of the ricefields; they showed what women can do.