Teilhard de Chardin was born in 1881 in Auvergne, France.

He walked the hills with his father, digging for stones and fossils, uncovering the ancient story of this land on which they lived. Teilhard later wrote that the wonder and amazement that this stirred in him became as much part of him as the colour of his eyes. This little boy, Teilhard, grew to become a man who, with wonder and amazement, explored the origin of humankind.

His mother taught him about God and the Church. He recognised the presence of God in all of life; he marvelled in the beauty of creation and of the Creator of all. But the findings of science contradicted some entrenched teachings of the Catholic Church.

Here is what I understand of his journey through life.

Taught by the Jesuits he gains a Bachelorette in Philosophy and a Bachelorette in Maths. Bright child.

As a boy of 18 Teilhard joins the Jesuit Community, he wants to be a Jesuit priest. There is long study and formation for such a calling. At the age of 30 he is ordained a priest, then begins work as a palaeontologist in the Museum of Natural History in Paris. His focus is the evolution of all life on earth.

The Great War disrupts all life in France. In 1915 Teilhard is conscripted to the army; he opts to be a stretcher bearer for rank and file soldiers at the front line of the battlefield, rather than a Chaplain Officer. He writes that once you have been close to such terrible carnage you are changed forever.

Three of his brothers die in battle, two are seriously injured. His mother says, ‘God must have something special for you’. Teilhard rests for a few weeks, then studies geology, botany and zoology at the University of Paris and completes his Doctorate.

He is invited to join a Jesuit scientist on a brief expedition to China. While travelling to their research site in Outer Mongolia on donkeys, they discover well preserved fossil remains estimated to be up to 750,000 years old. These provide new insights into evolution of life on planet earth, eons of time before the emergence of human beings.

Back in Paris, he teaches, writes essays, talks with colleagues and expects that this will be his life. Teilhard’s spirituality and his commitment to the world of science merge together. He writes to a close Jesuit friend, Pierre Leroy, ‘I can tell you that I am now living constantly in the presence of God’.

In 1923 Teilhard again has a short time of fieldwork in China. Back in Paris his teaching and writing are receiving more notice. Teilhard knows that he must move carefully. He is gaining respect as a palaeontologist and geologist, while the conservative theologians are advising the Vatican to maintain the story of Adam and Eve as historical fact, rather than as an ancient way of explaining creation and the Creator. Teilhard has moved outside the boundary of Catholic teaching.

Jesuit leaders respond to this challenge by posting him far from the intellectual discussions in Europe. Between 1926 and 1946 he is posted to China and for the last five years of his life to the USA.

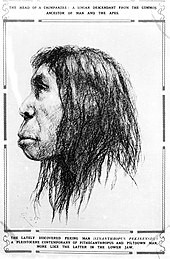

This separates Teilhard from theological debates in Rome and leads him to more field work and scientific discoveries. He is part of the team that discovers a scull of a prehuman creature, one step before the before the first human persons. Measurements of the spaces and contours of the skull indicate that this creature could stand upright and use tools. The discovery of Peking Man is world news, some call it the ‘missing link’. Invited to take part in Scientific Expeditions he travels widely in Africa and Asia.

During the years in China Teilhard writes two major books and numerous essays. He writes of evolution from the first signs of life to the emergence of self-reflective human beings. Then he outlines, based on the past, a future of ongoing evolution, humankind has not finished evolving. He proposes that the main cosmic energy that has united all elements at each step of evolution Omega Point of complexity and consciousness. The crunch point of the end of our world

During World War 2 Japanese occupiers in China hold Teilhard and his colleague Pierre Leroy in house arrest. At the end of the war, feeling some amount of hope, Teilhard returns briefly to France to again argue for publication, but the Church leaders will not budge. He will not be posted to any European institution, he will not be able to present his case to the Vatican.

He suffers a heart attack. On his recovery his Jesuit friends advise him to leave his collection of books and essays in safe hands so that they can be rescued if he dies. He is then posted to New York.

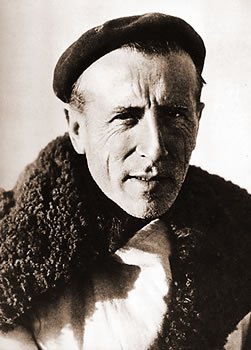

I like to think of this last part of Teilhard’s life as serene. He can walk in the beauty of nearby Central Park; he can spend time friends and colleagues who seek him out.

He has written scientific work and spiritual work which is followed one hundred years later. He will die without ever being assured that the work of his life will endure. At any stage Teilhard could have left the Jesuit community and continued in his career.

He is bow in 2024 widely regarded on the one hand as scientist and on the other as a deeply spiritual man. He could have married. He enjoyed the company of women and counted many as dear friends,. He could have separated his spiritual thinking from his professional writings in science. He didn’t. He was who he was, .In a final letter to the Jesuit leader in Rome he has simply stated his position according to his own conscience. He is quoted as saying, ‘The further I go in science the more I believe in God’.

In 1955 Easter Sunday is a sunny spring day. Teilhard joins with friends for Mass at the Cathedral in New York then a walk in Central Park, ‘soaking up the sunshine’. Nothing is unusual about this. Friends .invite him to dinner after this relaxed day together, While the meal is being prepared Teilhard collapses and dies.

Pierre Leroy takes the first available plane to New York to preside over his friend’s funeral. There are ten people in the Church. Friends.

Some day after we have mastered the winds, the waves and the tides and gravity

we shall harness for God the energies of love.And then

for the second time in the history of the world we will

have discovered fire.

Teilhard de Chardin