A young woman who came to Australia because she could not stay safely in her own country talks to me as I water my garden; I hear her worries and her hopes. No matter how hard she works there will never be the chance for her to work in the profession she had chosen. She holds to the anticipation that her children and her children’s children will have a good life in a good country. My great grandparents had similar worries and similar hopes. They would call themselves battlers.

During these 30 years of our family story all of the First Peoples of these parts of Australia lost country, lost freedom and lost the cultural connections of tens of thousands of years. I need to be able to write that as the major story of those years. This is a huge challenge.

Let’s start with my father’s grandparents on his mother’s side.

Honora Shea is an ‘Irish Orphan’ shipped to Melbourne by an Act of Parliament in London. ‘Poorhouses’ in Ireland are congested because of the potato crop failure, then the hunger, then the eviction of those who could not pay rent. Simultaneously in the new colony of Melbourne, there is a dangerous preponderance of men without wives. To manage these two issues the British powers that be, send impoverished young Irish women to Australia.

It is 1849. From the time Honora leaves the ship and stands on the sand in Williamstown, she feels the embarrassment of being looked at by so many men. Later the matron asks her, ‘Who do you fancy?” She replies, ‘George Walmsley seems a good man, but he isn’t a Catholic’. ‘That is the least of your worries,’ the matron says. ‘If you think he is a good man, then marry him’.

Does the matron know the whole story? Does she tell it? George Walmsley, born in Leeds in 1817 is, when young, convicted of the crime of stealing. He serves nine years as a convict in Tasmania and in 1847 comes, as a ticket of leave man, to Melbourne.

Honora and George marry at St Peter’s Anglican Church on the hill above Melbourne; they sign their certificate with crosses. They head, by oxcart, to a squatter’s property near Inverloch. George will work here. South Gippsland becomes the center for much of their family life though they spend some time on the goldfields, not finding gold but selling staple necessities to the miners. Honora’s twelfth baby, born there at the goldfields, is Charlotte, our grandmother. Honora and George settle in Korumburra and are respected in this township. When the Suffragists come to Korumburra to petition for women’s rights Honora signs her name to their list. She can write now.

George lives until after his 80th birthday. He suffers a heart attack while in another part of town and dies before Honora can reach him. She places a message in the Korumburra local paper: she grieves that she couldn’t say her last loving words to George or know his last breath.

My father’s grandparents on his father’s side.

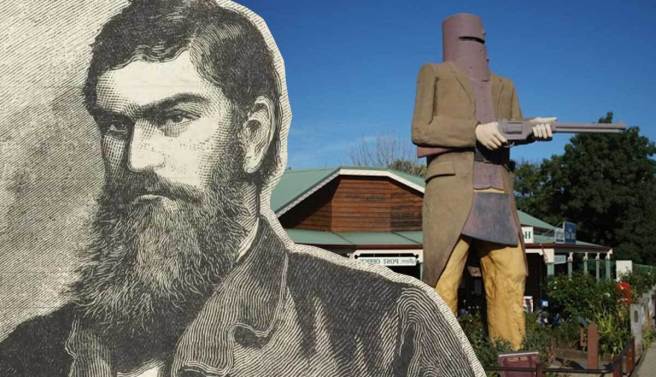

Mary Kelly of Galway disembarks in Melbourne in 1866 and settles in Bendigo. She is said to be related to Ned Kelly, so famous in this town. Though the peak time of the gold rush has finished, many Irish people are settled here and urge relatives to come.

Daniel Healy, the man who will be Mary’s husband, comes to Australia as ‘assisted passage’ on a ship called the Royal Dane. It berths in Williamstown in 1864 after an exceptionally rough voyage.

It seems that Daniel escapes from his bond when Queensland can no longer afford the cost of building more train lines, even with bonded labour. Eventually a Royal Commission examines transactions involving the Royal Dane.

The paying passengers disembark. There is a list. Daniels’ name is not listed. The Royal Dane then sails up the coast and the assisted passengers are faced with years of heavy labour to pay for the voyage. Queensland, newly separated from New South Wales, envisages a network of rail lines covering the vast distances. Heavy labour is needed for this ambitious plan. A deal is struck.

Daniel is listed as disembarking in Williamstown in 1866. He travels steerage on a small vessel and on arrival takes the road to Bendigo. He meets Mary Kelly newly arrived from Galway. Within two years they marry and raise a family of six boys and one girl.

Many workplaces have signs NO CATHOLICS NEED APPLY. Dan finds work in the railways. Mary Winifred, the only little girl of the family, dies when she is two years old. The six sons of the family join the railways, one by one.

Ned Kelly, the bushranger, is constantly in the news during the 1870s. Finally, he is arrested, brought to trial, convicted and sentenced to death. There are Healy relatives living in a small terrace house close to Spencer Street Station. A story passed down through all branches of our family claims that the Healys and Kellys gather there in 1880, on the day before Ned Kelly’s execution. They plan to march through the city, take over Government House, declare Australia a Republic, and pardon Ned. They are quickly dispersed by the police. ‘Such is life’, says Ned as he is about to die.

There is no record of what Dan says at that time though from time to time Dan protests against ‘the Royals’ by refusing to speak English.

Dan and Mary eventually retire to Moonee Ponds. Mary always cares for her skin during Australia’s harsh summers, she swathes her large hats with chiffon veils. It seems this is not enough to protect her Irish skin. The cause of her death is reported to be to be ‘skin cancer’. Dan finds it hard to live without her. He sells the Moonee Ponds house and moves to Brunswick where there are Healy cousins.

On my mother’s side there are great-great grandparents.

Annie O’Neill my great grandmother is born in Victoria, eight years after her mother, father, my great, great grandparents and two brothers, arrive from Ireland in 1841. Annie is my great grandmother, Australian from the start.

When gold is found in Ballarat the family heads for the goldfields. Father and sons pan for gold and protest for justice. They stand beneath the Southern Cross flag, burn their miners’ licenses in protest. Annie is a toddler; the family tent is inside the goldfield Stockade where the protesting miners, gather. Her brothers are armed. When the shooting between the miners and the soldiers erupts, Mick joins the thick of the fighting and is injured. Dan says, ‘I heard the shooting, jumped up, hit my head on the tent post and knocked myself out’. The O’Neill’ boys leave the family to seek a better life elsewhere; Mick joins the gold rush in California and fights in the civil war, Dan goes droving and shearing. They are lost to the family for decades.

Father, mother and daughter stay close to the diggings. As a lively red headed teenager Annie contributes to the family by working as a domestic servant for a household of miners who have ‘struck it rich’. She meets and falls in love with Franz Claus Stahl, a German citizen who jumped ship in Melbourne and headed to the gold fields. Annie is thirteen years younger than Franz. They marry. Franz builds a family home close to the Ballarat diggings. Annie Stahl gives birth to six children: a boy, four girls, then another boy. The Stahl family never ‘strike it rich’. The eldest son John joins with his father in working for wages in deep tunnels where threads of gold are commercially mined.

Franz becomes ill with a fatal lung disease brought about by inhaling the underground dust; his son John, now 19 years old, becomes the bread winner for the family. The Stahl family moves to Melbourne. John is employed digging underground tunnels for sewerage in Footscray. He dies in a tunnel collapse. The eldest girl, Margaret Ann Stahl, steps into the role of breadwinner and works as a servant for a rich family. She is my grandmother.

The story with the twist. The final ancestor on my mother’s side.

Matilda Meagher is our other ‘Irish Orphan’. She is shipped to Sydney, as Honora was shipped to Melbourne.

Matilda Meagher marries George Martin. They have one child together; he is named after his father, George Martin Junior. Matilda dies while the boy is still young. His father marries again. Young George dislikes his stepmother, finds his way to Melbourne, and is disowned by father and stepmother.

In Melbourne, George, who is artistic easily finds work painting murals on the ceiling of Southern Cross Railway Station. He finds happiness when he marries and starts a family of his own, but his young wife’s parents disown her for marrying someone they would not choose. The wife gives birth to a baby girl; there are complications after the delivery. She dies. George names the infant Matilda and carries her in his arms up the hill to Abbotsford Convent. He asks the Good Shepherd Sisters to care for Matilda until he can. This leads to another story, but not now.

When the artwork on Spencer Street Station is complete George walks the streets of Melbourne looking for work. There is a Portuguese owned pub with a sign outside CHEF REQUIRED. George smiles and turns away. The manager, a woman, calls to him and says, ‘I like the cut of you’. George protests that he is not even a shearers’ cook. ‘I will teach you’ she says. And so, with this coaching, and many hours of study in the State Library close by, George Martin becomes a skilled cook. Christmas comes. The Portuguese managers of the Pub always have a Christmas party and bring the domestic staff from their family home to help with the occasion. And so, it happens that George meets, dates and proposes marriage Annie Stahl, my grandmother.

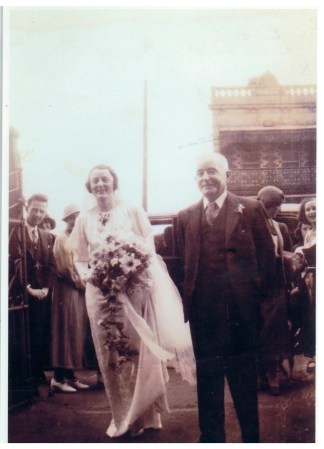

Annie and George bring Matilda home and together have two daughters and a son. When Vera, the eldest daughter marries Joe, her father George Martin walks her up the aisle.

.George holds me as soon as I am born, and when I can understand he draws pictures in a notebook to illustrate the stories he tells me.

I have a sense of my missing great grandmother, through her son, the artist and the nurturer, who loved Matilda Meagher, and loved me.