This is the first time I have attempted to write a story while it is unfolding. More than a month ago now Anne Goldfeld, a long-time friend who lives in Boston, sent a message. ‘When can we talk, face to face online?’ Of course we can talk immediately. We have been friends since we both worked in Site 2, a ‘refugee’ camp on the border between Cambodia and Thailand.

Anne looks deeply tired. I am watch and listen as she tells me that USAID funding for programs she she founded and worked for in Cambodia has ceased.

I hear her say:

‘The calamity has already happened. Out in villages throughout Cambodia there are 29 highly skilled medics, doctors and nurses now with no employment and no salary. There are 239 critically ill patients for whom medical care will cease. Normally this program brings cures to the majority of the patients. Treatment is given, is supervised and side effects of the medication are monitored. Without this care patients are expected to fare poorly. This dreaded disease will spread through the communities. Many will die’.

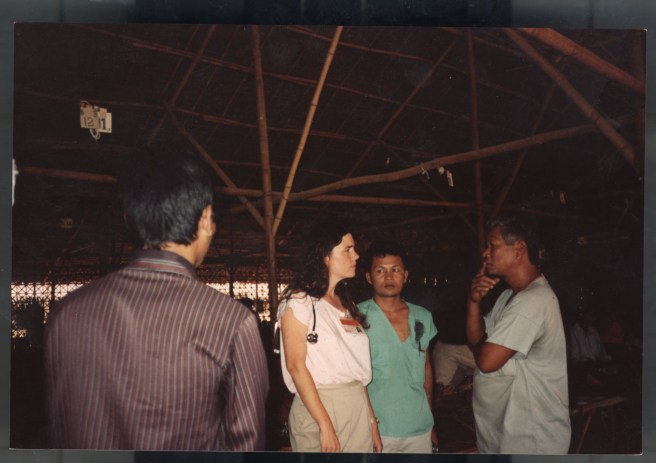

I need to listen and to understand. . Anne and I I first met in 1989 when Anne became medical coordinator for the American Refugee Committee in Site 2.

There was a bamboo and thatch hospital; it was responsive to dire emergencies including immediate care for patients carried in bleeding from landmine injuries. As well there was a Tuberculosis Clinic initially set up by Bob Maat. During a decade or so while the camp was under constant shelling, Bob taught a team of Cambodian refugees to care for patients infected with TB. These refugee medics understood the disease and ensured that patients took their medication on time and consistently. Almost all were cured. Even if the area became an active battle zone there were strategies for Daily Observed Therapy. Sok Thim, refugee and medic, learned to be a leader in this program; Bob moved on to other tasks. By the time the border camps closed, 10,000 patients had been treated in refugee camps along the border. Most lives were saved.

Already, early in her career, Anne worked at the interface between scientific research in her lab in Boston and caring for patients in the most dangerous of places. On one hand she was a skilled physician in dire circumstances, and on the other hand a respected scientist at Harvard who used her scientific skills to save lives. All that endangered life mattered to Anne. The territory near the camp was riddled with land mines; she called the deaths from mine injuries a ‘preventable’ medical epidemic. She documented what she saw in Site II, exposed the humanitarian toll of landmines and called for their international ban.

We have been friends for thirty-five years now. I have often watched Dr. Anne working. The word that stays with me is ‘compassion’.

Inside Cambodia relative peace was restored in the early nineties but there was no TB treatment available in rural villages where 80% of the population lived. I remember that in 1994 Anne and Thim founded a local organisation which they named the Cambodian Health Committee. It brought community-based TB treatment, similar to that in the border camps, to the most impoverished and TB-infected regions of the country. The progress in reducing TB infections in Cambodia during the 1990s and 2000s was formally recognised by the World Health Organisation.

The next challenge for Anne and Thim was the dual diagnosis of AIDS and TB. Anne worked diligently as physician with laser focus to provide care and access to medicines for HIV and as a scientist to research the most effective way of treating patients with both infections. Once again lives were saved.’

In Cambodia there was another urgent problem still to be resolved. A small percentage of TB patients worldwide are resistant to the usual TB treatment regime. This was a difficult but necessary challenge. The work with drug resistant TB (DR-TB) that Cambodian Health Committee (CHC) started has saved thousands of lives. The Global Health Committee, founded to bring CHC’s lessons to Africa, began similar work in Ethiopia, but that is too long a story for me to tell now.

During the past five years in Cambodia USAID has funded CHC’s DR TB Program. It has been highly successful. Last October it was funded for another five years.

Now, in this crisis I knew that what I was hearing was vital. I kept a notebook and pencil on hand.

Eventually I asked Anne ‘What did you do?’

‘I immediately began to search for funds to prevent an interruption of the DR-TB treatment. Interruption can lead to death and to developing even more resistant and even untreatable drug-resistant TB that could easily spread. I talked with Dr. Rocio Hurtado, a clinical advisor to CHC since 2010, and Dr. Sam Sophan, CHC’s Lead DR-TB clinician and clinical manager of the Cambodian countrywide program’.

I can see that it was a race against time.

‘By March 1st we were together in Phnom Penh. Rocio, Sophan, and I got in the truck and just headed west to Battambang, traversing the villages on the way where the sickest patients live. We veered off the highway onto roads to distant villages, and, over the next days we visited patients in hospitals and in their homes around Battambang, Mongkol Borei, and Siem Reap, and along the way back to Phnom Penh’.

‘Patients and their families were deeply involved with their treatment and were trying their best under the new circumstances. But, with no funds for a health worker to check-up on them, for transportation to regional hospital for lab tests, or for extra nourishing food, which is essential in treating DR-TB, their care was sadly compromised’.

I have been on one of those village journeys with Anne. It involves rugged muddy or dusty tracks. Try not to imagine a ‘village’ with streets and fences. Instead imagine a clump of thatched or tin-roofed dwellings at the end of a dirt track. Imagine that as Anne and her colleagues work with a patient there are likely to be chickens and farm animals nearby and there will certainly be children wanting to watch as the patient sits on a mat beside the doctor. There is little shelter from the tropical heat. From a respectful distance I have watched Anne, masked and with stethoscope ready, talking quietly. Her patient is also masked up. Anne offers dignity and hope in the most primitive of circumstances. I keep listening to the story, imagining myself there.

Out in the villages away from main roads you still find extreme poverty. You need to live among it for days and nights to understand. Before it is light people light candles to begin the tasks of the day. There are seasonal ‘hungry times’. During harvest season there is a chance to be hired as a worker, but after harvest there is little alternative other than making or cooking or growing something to be sold in the local market. Parents and grandparents and school aged children seek ways to keep the family fed. They may have a few chickens but cannot hope for more assets.

The first, and only main meal of the day will likely be at 11 am. A family with an able-bodied person: a father who can cross the border to Thailand to work as an exploited labourer; or a daughter who can work in the sweat shop factories in Phnom Penh have at best some precarious security. Many families, still with no electricity or running water, hope that their child will be educated and find work that brings in real money. For a mother alone with children to care for, there is little hope to hold. But they keep up appearances. They sweep the bare earth around their little hut-on-stilts lest a child step on a scorpion, they wash their sarong and the child-clothes and pin them out on a line. Neighbours walk to work, threading their way between these small dwellings. If fortunate they may carry, for example, bananas and batter on one shoulder pole and a terra cotta pot with glowing charcoal on the other. Such an asset should bring enough money for food for a day.

Anne understands this.

‘What we did had impact. We reviewed each patient’s progress on therapy, checked and changed medical regimens because of side-effects, poor response to treatment, or because of worrisome features of their infection, and we organized necessary lab tests so we could know that they were responding favourably to the drugs. We provided both emotional and economic support for food. We provided clinical and logistic support to the medical team, who are not receiving a salary.’

I can hear the exhaustion in Anne’s voice as she lands back in Boston.

‘I’m going to California straight away. There are supporters there who might help to find donors’.

I wish Anne could stop and rest. It is Easter Saturday here. We know that it is sacred time for both of us.

‘My Passover is finishing as you celebrate Good Friday and Easter Sunday. It is Ethiopian Orthodox Good Friday and Khmer New Year too!’

In the Australian press, Elon Musk, one of the richest people on Earth, is reported as saying: ‘The fundamental weakness of Western civilisation is empathy’. We know that this story that Anne has told and I have written, is a story of empathy. It is surely central to any civilised society. Anne has the last word.

‘I wish Elon Musk could join the team working on the ground out there in Cambodia. It might change his perspective’.